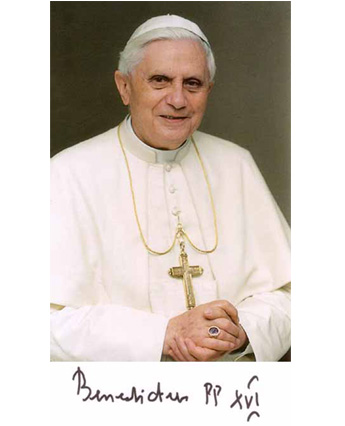

After six years of public silence, broken only by a few mild personal comments, Pope-emeritus Benedict has spoken out dramatically, with a 6,000-word essay on sexual abuse that has been described as a sort of post-papal encyclical. Clearly the retired Pontiff felt compelled to write: to say things that were not being said. Benedict thought the subject was too important to allow for his continued silence.

Vatican communications officials thought differently, it seems. Benedict’s essay became public on Wednesday night, but on Thursday morning there was no mention of the extraordinary statement in the Vatican’s news outlets. (Later in the day the Vatican News service issued a report summarizing Benedict’s essay; it appeared “below the fold” on the Vatican News web page, below a headline story on relief efforts for cyclone victims in Mozambique.) For that matter it is noteworthy that the former Pope’s statement was not published by a Vatican outlet in the first place; it first appeared in the German Klerusblatt and the Italian secular newspaper Corriere della Sera, along with English translations by the Catholic News Agency and National Catholic Register.

Benedict reports that he consulted with Pope Francis before publishing the essay. He does not say that the current Pope encouraged his writing, and it is difficult to imagine that Pope Francis was enthusiastic about his predecessor’s work on this issue. The two Popes, past and present, are miles apart in their analysis of the sex-abuse scandal. Nowhere does Benedict mention the “clericalism” that Pope Francis has cited as the root cause of the problem, and rarely has Pope Francis mentioned the moral breakdown that Benedict blames for the scandal.

The silence of the official Vatican media is a clear indication that Benedict’s essay has not found a warm welcome at the St. Martha residence. Even more revealing is the frantic reaction of the Pope’s most ardent supporters, who have flooded the internet with their embarrassed protests, their complaints that Benedict is sadly mistaken when he suggests that the social and ecclesiastical uproar of the 1960s gave rise to the epidemic of abuse.

Those protests against Benedict—the mock-sorrowful sighs that we all know sexual abuse is not a function of rampant sexual immorality—should be seen as signals to the secular media. And secular outlets, sympathetic to the causes of the sexual revolution, will duly carry the message that Benedict is out of touch, that his thesis has already been disproven.

But facts, as John Adams observed, are stubborn things. And the facts testify unambiguously in Benedict’s favor. Something happened in the 1960s and thereafter to precipitate a rash of clerical abuse. Yes, the problem had arisen in the past. But every responsible survey has shown a stunning spike in clerical abuse, occurring just after the tumult that Benedict describes in his essay. Granted, the former Pontiff has not proven, with apodictic certainty, that the collapse of Catholic moral teaching led to clerical abuse. But to dismiss his thesis airily, as if it had been tested and rejected, is downright dishonest.

Facts are facts, no matter who proclaims them. The abuse crisis did arise in the muddled aftermath of Vatican II. Benedict puts forward a theory to explain why that happened. His theory is not congenial to the ideas of liberal Catholic intellectuals, but that fact does not excuse their attempt to suppress a discussion, to deny basic realities. (Come to think of it, this is not the first time that the public defenders of Pope Francis have encouraged the public to ignore facts, to entertain the possibility that 2+2=5.)

That message—the message of Pope-emeritus Benedict—is a striking departure from the messages that have been issued by so many Church leaders. The former Pope does not write about “policies and procedures;” he does not suggest a technical or legalistic solution to a moral problem. On the contrary he insists that we focus our attention entirely on that moral problem and then move on to a solution which must also, necessarily, be found in the moral realm.

As background for his message, Benedict recalls the 1960s, when “an egregious event occurred, on a scale unprecedented in history.” He writes about the breakdown in public morality, which was unfortunately accompanied by the “dissolution of the moral teaching authority of the Church.” This combination of events left the Church largely defenseless, he says.

In an unsparing analysis, Benedict writes of the problems in priestly formation, as “homosexual cliques were established, which acted more or less openly and significantly changed the climate in seminaries.” He acknowledges that a visitation of American seminaries produced no major improvements. He charges that some bishops “rejected the Catholic tradition as a whole.” He sees the turmoil as a fundamental challenge to the essence of the faith, observing that if there are no absolute truths—no eternal verities for which one might willingly give one’s life—then the concept of Christian martyrdom seems absurd. He writes: “The fact that martyrdom is no longer morally necessary in the theory advocated [by liberal Catholic theologians] shows that the very essence of Christianity is at stake here.”

“A world without God can only be a world without meaning,” Benedict warns. “Power is then the only principle.” In such a world, how can society guard against those who use their powers over others for self-gratification? “Why did pedophilia reach such proportions?” Benedict asks. He answers: “Ultimately, the reason is the absence of God.”

It is by restoring the presence of God, then, that Benedict suggests the Church must respond to this unprecedented crisis. He connects the breakdown in morality with a lack of reverence in worship, “a way of dealing with Him that destroys the greatness of the Mystery.” Mourning the grotesque ways in which predatory priests have blasphemed the Blessed Sacrament, he writes that “we must do all we can to protect the gift of the Holy Eucharist from abuse.”

In short Pope-emeritus Benedict draws the connection between the lack of reverence for God and the lack of appreciation for human dignity—between the abuse of liturgy and the abuse of children. Faithful Catholics should recognize the logic and force of that message. And indeed Benedict voices his confidence that the most loyal sons and daughters of the Church will work—are already working—toward the renewal he awaits:

If we look around and listen with an attentive heart, we can find witnesses everywhere today, especially among ordinary people, but also in the high ranks of the Church, who stand up for God with their life and suffering.

Still the renewal will not come easily; it will entail suffering. For Benedict, that suffering will include the waves of hostility that his essay has provoked, the dismissive attitude of much lesser theologians, the campaign to write him off as an elderly crank. No doubt the former Pope anticipated the opposition that his essay would encounter. He chose to “send out a strong message” anyway, because suffering for the truth is a powerful form of Christian witness.

Source:

https://www.catholicculture.org/commentary/otn.cfm?id=1338